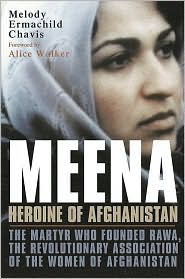

Meena, Heroine of Afghanistan, a new book by Melody Ermachild Chavis

March 1, 2004

Click here to purchase a copy of the book.

Click here for more information.

Book Description

Meena founded the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan in 1977 as a twenty-year-old Kabul University student. She was assassinated in 1987 at age thirty, and lives on in the hearts of all progressive Muslim women. Her voice, speaking for freedom, has never been silenced. The compelling story of Meena’s struggle for democracy and women’s rights in Afghanistan will inspire young women the world over.

Meena, Heroine of Afghanistan is a portrait of a courageous mother, poet and leader who symbolizes an entire movement of women that can influence the fate of nations. It is also a riveting account of a singular political career whose legacy has been inherited by RAWA, the women who hold the keys to a peaceful future for Afghanistan. RAWA has authorized this first-ever biography of their martyred founder.

A radical passion for justice

LA Times Book Review by Susan Griffin, March 2004

On the surface, “Meena, Heroine of Afghanistan” is a very simple book. Since this account of the life of the founder of the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan, or RAWA, is told for girls as well as women, the style is conventional and direct. Yet the narrative will provide a profoundly moving experience for readers of any age. In fact, the story of the young woman who at the age of 20 started the first movement for women’s rights in Afghanistan, only to be assassinated 10 years later, is a page turner.

Meena’s story cannot have been easy to piece together. Readers will benefit from the experience of the author, Melody Ermachild Chavis, who in her career as a private detective has investigated numerous murder cases. In the course of her research for this book, she traveled to Afghanistan to interview many of the principals — men and women who, even after the Taliban was overthrown, were still in danger of attack by fundamentalist terrorists because of their support of women’s rights.

Those readers unfamiliar with the lot of women under the Taliban will be shocked by the conditions revealed in this book. Yet the logic of the oppression will not, unfortunately, be entirely unfamiliar to Westerners, who see various forms of repression imposed on women in Christian fundamentalism and ultra-Orthodox Judaism. Claiming that women are spiritually and intellectually inferior as well as sexually dangerous, the Taliban promoted male domination both in the family and in public life through various forms of repression, including the imprisonment of women in the home, the imposition of the veil and the burka, the denial of the vote and of education, the exclusion of women from the clergy and places of worship, and opposition to abortion, affirmative action and the employment of women outside the home.

In 1957 — the year Meena was born into a middle-class family in Kabul — Afghanistan was ruled by King Zahir Shah, a monarch who supported some measure of equality for women. Afghanistan’s modern history can almost be read as an exercise in violent ambivalence concerning democracy and women’s rights. Amanullah Khan, who ruled Afghanistan from 1919 (the year the country won full independence from Britain) until he was deposed in 1929, began a program of modernization that included education for women. Nadir Shah, king from 1929 to 1933, abolished Amanullah’s reforms, but Nadir’s son Zahir, who succeeded him after Nadir was assassinated, advanced Amanullah’s liberalizing policies even further, establishing a constitution in 1964 that gave women the right to vote.

It was thanks to these innovations that Meena received an education — unlike her mother, who was illiterate. Lycee Malalai, the all-girls school she attended, was named for an Afghan heroine who in 1880, when the country was invaded by Britain, had retrieved under gunfire a fallen Afghan flag and held it high until she was shot down by British soldiers. Inspired by this story and by two of her teachers who believed in the equality of women, Meena eventually became a heroine herself to countless Afghans, legendary even before her martyrdom at age 30.

After graduation, Meena intended to study law so that she could fight for women’s rights in the courts. But by then the liberal atmosphere that had fostered her determination had dissipated. Three years earlier, Zahir was overthrown by his prime minister and cousin, Mohammed Daoud, who was aligned with a pro-Soviet party. Gradually Afghanistan lost its independence, and the government became unstable. Fundamentalist groups began interpreting every democratic reform as a sign of corrupting foreign influence, and emancipated women were their first targets. By 1976, when Meena entered the University of Kabul, its female students had to contend with a reign of terror as random attacks were carried out on them. The followers of the Islamic radical Burhanuddin Rabbani threw acid on the exposed legs and even the faces of women walking across the campus — the beginning of hostilities that continue to this day.

Meena did not let these attacks stop her from attending the university or from speaking out for women. The resolve and bravado for which she was soon to become famous showed itself in a family drama culminating that year with her marriage. Meena was 19 years old. Because according to Afghan tradition a girl is considered marriageable at 13, the pressure from members of her extended family for her to wed had reached a fever pitch.

Meena’s standards seemed impossible to fill. She did not believe in, nor would she consent to, a bride price, let alone an arranged marriage. She would not wear the veil; though polygamy was still the custom in many households, she insisted that her husband should take no other wives; she demanded that she be allowed to continue her studies; and she made it clear that she planned not only to practice law but to hold her own political views as well. Eventually an enterprising aunt found Meena an acceptable husband in Faiz Ahmed, a distant cousin who was a doctor with radical views, including a belief in women’s rights. Because he agreed to all her conditions and she liked him, Meena agreed to the union, though in the beginning she was not in love with him.

If over time she would come to love Faiz, she never agreed with his Maoist politics. She seems to have rejected ideology altogether, favoring instead the complexities that inform the lives of real women. Still, she watched and learned from her husband’s political activism. Increasingly, it seemed to her that the courts were not the only way to better women’s lives. She decided to start a political organization for women. Influenced by her husband’s organization, which under a pro-Soviet regime had to be clandestine, she found a way to build RAWA while keeping its membership secret. Interestingly, her method was similar to one used by American feminists of the late ’60s and ’70s: a constellation of small groups. Though Meena met with all the groups, they did not meet with one another, making it easier for women to keep their membership secret and thus evade the disapproval and draconian retaliation of their families. This approach also afforded great intimacy, which helped give its members an uncommon strength and courage.

In the beginning, some of Meena’s tactics, such as wearing a burka when visiting members’ houses, seemed unnecessary, but soon the wisdom of this approach became all too clear. When Daoud was assassinated in 1978, thousands of Afghan intellectuals were imprisoned or executed. The following year, after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, all other political points of view were brutally repressed. That officially the Soviet regime supported women’s rights made RAWA’s task no easier. Indeed, educating women about their rights became more difficult under a hated government that was forcing its ideological program on an occupied people.

Soon Meena’s life became more difficult in still other ways when, because he was a Maoist, Faiz and Meena were forced to separate. Meena continued to organize women, even during the last month of her pregnancy. On the day her labor began, Faiz was arrested. Fearing that she too would be imprisoned, Meena went to the hospital at the last minute before giving birth, leaving in disguise only hours afterward. In one of the more wrenching episodes of her story, she decided to leave her newborn child with a friend before going into hiding herself. Faiz was finally released from jail, but he was able to visit his wife and daughter only briefly before he fled to Pakistan.

Though matters would soon become significantly worse under the warlords and fundamentalist mujahedin who finally overthrew Soviet rule, under Meena’s leadership RAWA continued to publish and distribute leaflets, hold literacy classes and build its organization through the continual spawning of small groups of women. Eventually Meena herself was forced to go to Pakistan. But she continued to work for RAWA there, establishing literacy classes and a home for refugee Afghan women and children. She was close to finishing work on a hospital intended to serve refugees and those injured by land mines when she was murdered by an Afghani who had been acting as a RAWA supporter.

The author’s description of Meena’s considerable physical beauty, burnished by a passion for justice that gave her a luminous quality, is verified by the photographs accompanying the book. As one learns about how she would go out dressed as a man, or show up at the home of a member who was ill or suffering a loss, bringing food or offering to cook, even while she was pregnant and exhausted, one comes to love this woman.

There is no comfort in the supposition that since Meena was a political activist, her suffering must have been exceptional. A piece about Afghan women written by Jane Kramer for the New Yorker makes it clear that over the last two and a half decades most of the women of Afghanistan have suffered terribly, often in almost unspeakable ways. Kramer quotes Zahir Tannin, once editor of a prominent daily paper in Kabul and now head of the Afghan desk at the BBC: “No one wants to talk about it but the one thing [Afghans] do agree on is that the biggest victims of our twenty years’ war are women.” If Meena was exceptional it was because she fought back and took joy in the fight – – a joy shared by the women of RAWA, who, as they continued Meena’s work under the Taliban, chose as an act of defiance to wear bright toenail polish under the burka.

In her moving foreword to the book, Alice Walker writes, “One day one hopes the whole of Afghanistan, healed after so many centuries of war, will look upon the smiling radiant face of Meena and recognize itself.” If, as Walker writes, the male leaders of Afghanistan live “under the illusion that she is separate from them,” so too does the current world leadership. The 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the status of refugees still defines “refugee” as someone running in fear from persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, even membership in a particular social group or because of holding a political opinion, but not persecution due to gender.

The world would do well to take this widespread persecution seriously. Its victims are also often startlingly prescient. What would have happened had world leaders listened to Meena in 1981, when, after attending an international conference of socialists in Paris to protest the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, she warned in a televised interview of the dangers of violent Islamic fundamentalist movements? When Afghanistan’s public educational system collapsed, Meena and others in RAWA saw the danger, but the American government took no heed. Despite pleas for help, no money or support was given to RAWA for its schools and hospitals. Yet the Islamic fundamentalist schools, established during the Soviet occupation by, among others, Osama bin Laden — and that trained many future terrorists — were well funded by several nations, including our own.

This is a book not only to read but to urge others to read. It provides, in its devastating way, a measure of hope. Another way of preventing violence exists: not through repression but through the expansion of civil liberties.

Susan Griffin is the author of several books, including “A Chorus of Stones” and, most recently, “The Book of the Courtesans.”